Liner Notes: Laura Burhenn of Mynabirds

The Honeydogs frontman talks about the band's new album and a whole lot more.

Welcome to Liner Notes, where we interview music-obsessed curators and artists. In each interview, we get their three independent artist picks and learn about how their relationship with music impacts their lives.

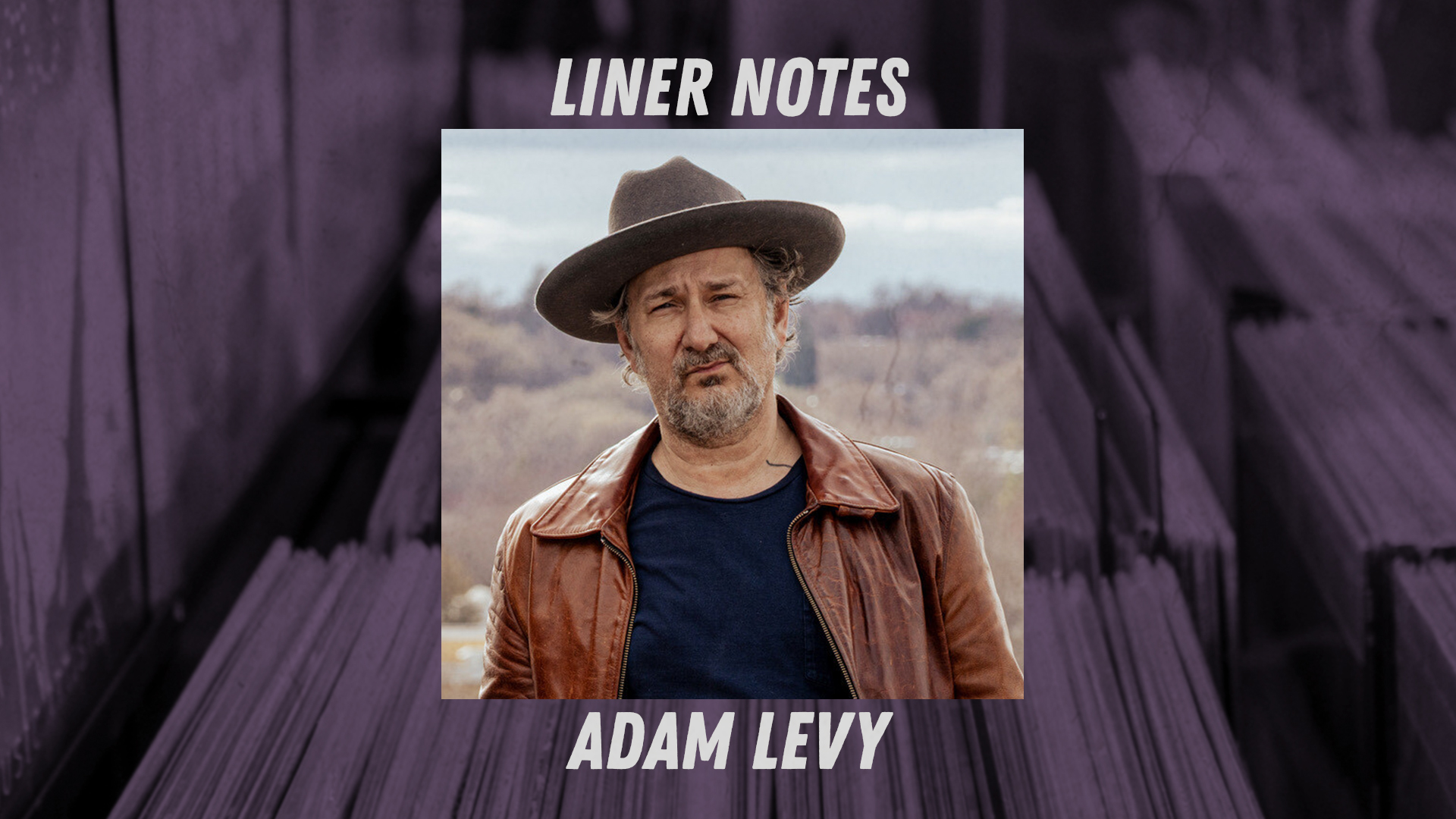

For this installment, we're speaking with Adam Levy, frontman for the Honeydogs. Stalwarts of the Minnesota music scene since the mid-'90s, they released a pair of indie records before signing with Mercury for 1997's "Seen a Ghost." From there, they moved to Rykodisc's Palm imprint for 2000's "Here's Luck"; the years since have seen them releasing a series of albums that have deepened and refined their eclectic, rootsy sound. Levy was an uncommonly gifted songwriter 30 years ago, and if anything, the ensuing decades have further set him apart.

Adam joined us to talk about the band's latest album, the recently released "Algebra for Broken Hearts," which reunites their original lineup for the first time in years. To say it's an improvement over its predecessors would imply that there was anything wrong with them — better, then, to say the new record sounds like a homecoming, a tuneful resumption of unfinished business that's being pursued by partners who never stopped loving the noise they make when they're together.

The first thing I want to say is something that I say generally whenever I talk to artists who have been around for a while, which is just, thank you for making a record. It's my preferred way of listening to music, and there's less and less incentive for artists to do it anymore.

Yeah, mean, at a certain point, making albums becomes somewhat of a vanity project just because you're not going to be selling hundreds of thousands, let alone, you know, millions. So you do it because you love it. And that's why I keep doing it.

This relates to something else I want to talk to you about, which is that your career arc has kind of — I would assume, unhappily for you — traced a really… unprecedented unusual period in the record industry. You you started out, you did the traditional thing. You know, made an indie record that got attention, you signed the major label deal, and then, you know, that's the end of the '90s, and then things start going haywire for a minute. And then it's all indie from there on out.

The band has dealt with the frustration of releasing new music into an environment where on one hand technology had made it possible for a group like the Honeydogs to self-release, but on the other hand, technology has made it harder than ever to make money doing that. So I wanted to kind of get your thoughts on that, because one of the big things that we're trying to do at Harmonic is make it a little easier for artists to get paid.

Well, bless your heart. It feels like there's been economically diminishing returns as you continue to make music. But I think you just do it, you know. You try to figure out ways to make it worthwhile. Playing more shows. The only way we really make money now is by playing shows, and it feels like you're doing direct advertising as a live performer to sell your records. And most of those CDs are getting sold at shows because people want to walk away with some artifact from your show.

But I just have always wanted to make something that means something.That I'm going to want to listen to. I'm lucky to have children who listen to my music, which is really nice because I feel like if I'm not doing anything else, I'm making music for my grandchildren to listen to. My observations about the world might not be worth anything, but at least my children respect and listen to what I do. And it's kind of shaped their consciences.

My daughter is a songwriter as well. And she's kind of entering into this whole world where I keep saying "Make an album, make an album," but she just releases singles. That's all she really wants to do at this point. Although, you know, she grew up listening to Nick Drake albums and the Beatles and all that. So she understands how great albums are, but I think she sort of… the economics of it just don't make sense. You know, whereas old farts like me are like, "No man, you gotta do a record. It's a batch of songs. It's a concept."

It's a whole thing. And I just am never going to stop doing that. I'm in another band, Turn, Turn, Turn, and we do singles. And I've just been kind of struggling. Like, really? Do we want to do singles? Nobody that's listening to our music is really going to listen to the singles in the same way that they're going to listen to the albums once we put the LPs out. But I've got younger bandmates, so I have to listen to them.

You said about a hundred things that I want to touch on, but the last thing that you talked about was singles. One of the things that I struggle with overall is that the release cycle is not what it used to be. I mean, when you were on Mercury and you'd release a single, that meant something — back then, you were putting out kind of a teaser for the record. Trying to induce consumers to buy the thing.

Now, what is a single's purpose? Because it's not that anymore. Anybody can listen to the whole damn thing whenever they want. And I think as a result, the release cycle, the ability for an album to hold people's attention for an extended period of time, I feel like that's a struggle. How do you feel about that?

Yeah, it's been a struggle for some time. I think the reason people put singles out is just to sort of stay on the radar, just because there's such a glut of music. And either you sort of like go away for a little while and then put an LP out, or you try to percolate in social media and stay on people's radar and just keep releasing new material. And I sort of feel like it's different with different audiences, you know, with older audiences, that sort of single thing is not as resonant as putting a record out — people will wait for the record even if it takes two or so years for the next one to come out. They're just not so interested in streaming the latest singles.

We've got a creative… I want to call it a creative economy. It's not really a moneymaking economy, but it's a creative — what's the word I'm looking for — kind of paradigm where in order to stay relevant, you have to keep releasing material. It's like, we've got a show coming up; we can pair that with a single or something like that. So it sort of becomes like an advertising strategy.

I think back to when I was a teenager and there were albums that I would listen to for an entire year, and now, even if it's something that I love, maybe I'll listen to it for a couple of weeks before the next thing comes along to get my attention. Is it the same way for you? How long does a new piece of music sit with you?

It's a really good question. I think when I look at my Spotify playlists — I make a couple of those every year, and each one has about 100-plus songs on it. And there are some things that I put into collections three years ago that still sound awesome to me. And there's some things that just kind of don't quite hold up.

I would say I try really hard to listen to a lot of new music and not get stuck in the cycle of the music that influenced me and my songwriting, for a couple different reasons. I just kind of want to see what other people are listening to. And oftentimes I get great ideas. There's this songwriter Samia, who my daughters have become really good friends with, and she's kind of exploding right now all over the country. When I first heard her, it kind of didn't move me at all, but with successive listenings, it's like, "Wow, she's got beautiful melodies and cool chord changes." And so I'm trying to just open myself up more to listening to other things, just to kind of expand my own horizons, so I don't end up going back and trying to find obscure, cool 1960s and '70s music.

But there's also the part that you're talking about successive listens. Spending time with a piece of music. I think that's a lot harder now, because all you have to do is just hit a button if you get bored or you don't like something immediately. It's easier not to give something time to get its hooks in you.

Right, and I still think the way I write music and record it is with that idea in mind. That you want something to have sustainability so that in terms of lyrical content, there's layers of meaning people have to kind of chip away at and they might not get it the first five times they listen to it. Instrumental layers where there's just little fairy dust you've sprinkled on it just to kind of keep people interested.

Every song that I write, I like to sort of treat it as a little bit of both a puzzle to be deconstructed and reconstructed, and also as a journey just for people. Like I'm taking somebody on a little bit of a trip, whether it's the touring of a house or something where you're like, "Check out this living room, it's really cool" and then "Look at this kitchen," and then "Whoa, look at the bathroom, it's freaking amazing."

That's kind of the way I like to write songs. They surprise the listener. They sort of take them on a little bit of a journey. So that's not going to stop. I'm going to keep doing that.

For a band of brothers like this, both literal and figurative, I think there's something really beautiful in making an album just because you want to and because it feels good to make music with those people. I can only imagine that it must have been a little different starting out. You have to worry about what the label thinks. You have to worry about sales figures. You have to worry about video budgets and stuff, and now it's just out of love, which I think is beautiful.

Where did the material come from for you? I know the songwriting was more democratic this time, but did you have this material waiting to be recorded, or did you write specifically for a new album?

I'd say most of the material was there, just since I've got multiple projects. I'm always writing music, and I've always got a lot of material to dig through. The only song that I wrote for the sessions was actually written like the third day of recording, when the producer said, "Hey, I think you need one more song."

There was a part of me that was super irritated. "What do you mean? Is this chopped liver? We just gave you like ten really what I feel like are pretty good songs." He's like, "No, just go home and do it. You can do it, I know you can write a song." I was really irritated, and I went home and I punched a pillow and was just kind of cursing John Fields' name for a bit, and then I just dug in and started writing something, finished it over coffee in the morning, and brought it in to record and played it once for the band, twice for the band, and then we just started playing it and recording it. And so it feels like there's a kind of new energy urgency about that song.

I love giving people music in the studio without giving them a long time to sit with it and second-guess what they're going to play. Their first instincts are what they go with. And frankly, this group of players, we've had so much time together. We've listened to so much music together. We've made so much music together. People's first instincts are their best, I think. And everybody has lots of really great ideas. And so that song came together really quickly.

And I would argue, you know, even if some of these songs were written a few years earlier, when the band got their mitts on them, everybody kind of did their own thing. They sound different than the demos that I brought in, or that Tommy brought in, for us to learn the songs.

What will it take at this juncture for another Honeydogs album? What are your metrics for success, and what's going to enable you to continue in this vein?

I think just everybody in the band feeling really good about what we delivered. We were debating doing some long tours. I'm still gonna do some radio stuff around the country, but I don't think we have plans for a really big tour. Mostly just regional stuff we're gonna be doing this coming December.

The measurement of a good record is only going to be how much we feel good about it, really. Just like, "Was that fun? Does it sound great?" And I think it meets those criteria. A lot of times you record an album, then you're like, "Shit, I don't know if we can do this live. This is just too hard." But this music was pretty easy.

We were able to do a lot of these songs in just a couple of rehearsals. And part of that is just getting older, I guess, and more comfortable with your instrument. But I also think we're pretty capable of replicating the things that we're recording. So as far as are we going to do this again, I think the answer is a hard yes.

It's a matter of when are we going to have time? I certainly have a lot of songs right now that we can work with, and I'm writing more stuff too, and Tommy, who brought in a couple of really great songs on the last session, also has songs. So I think we'll just find time to do it. If I had to guess when we will record, it would probably be next summer. My brother's very, very busy with music. He's playing, I don't know how many shows my brother plays a month, probably close to 15 to 20 shows a month with all different artists. So he's learning a lot of music, playing a lot, and he's recording at his house. He's pretty busy. Trent lives in Nashville. Tommy lives in Houston. And so getting the band together requires plane tickets and, you know, eking out a little bit of time here and there.

But I think the last time we were together, actually for rehearsals for the release show, we went out for a drink with John Fields and said "When are we gonna make the next record, John?" He's like, "I'm ready, let's do it."

I want to get back to what you said about your kids and wanting to leave lasting statements, because I have to tell you that your solo album [2015's Naubinway] is… you know, I wanted to write about it but I couldn't find the words. It's one of the most powerful records I've ever heard. So, you know, thank you for having the strength and the willingness to put it out there.

Thank you for listening.

It's weird to think that that was about 11 years ago when that record came out, and some of it feels really raw still. Honestly, when I made that record and released it, I felt really comfortable playing all those songs, and now 11, years later, for some reason there's a rawness that makes it really hard to play those.

I don't know if it was because I was in the fog of grief and the only thing that I saw being able to heal myself was to immerse myself in something that I feel comfortable doing. But now when I listen to those songs, it's like, wow, that is so, that's so vulnerable. I don't know if I feel comfortable being that vulnerable.

You know, I think with time, your emotions kind of change in grief. And I miss my son very differently than I missed him then. Sort of felt like his leaving us was a relief for all of us, for him included, obviously. You know, he was in such pain that for him to take his life was a way to kind of get some control over all of that pain he was feeling. And I think we had just borne witness to this painful couple of years, just watching him agonizing through his art and his behavior. We were so sad that we couldn't do anything about it. Watching your child in pain is like one of the worst things that a parent can experience.

So yeah, like those songs feel… there's a certain amount of… what's the word I'm looking for? Sacredness is the wrong word. It just feels like I shouldn't touch them, that they just, there's something that just sort of exists as a recording and that I shouldn't play them live. Although occasionally I will play a couple of them now and then.

That all makes sense. You're an artist, you're a musician. And so it's almost like the first few seconds after you have a wound, you know, the real pain hasn't quite set in yet. Your instinct is to go back to that thing that has always brought you comfort, and you have this active communion with the muse. I can completely understand why it would feel… a lot more difficult to go back to that material now, but god, that album is just, I'm so glad it's out there.

Thank you. Thanks a lot.

I know I need to let you go soon. But before we go, do you have three indie artists that you can recommend?

Indie is a weird word. You know, like I was mentioning Samia, who I really, I really like. And part of it is because like I've gotten to know this kid. She's just a really talented songwriter and a really good soul. Samia is awesome. I love St. Vincent. but St. Vincent is making a lot of money touring, so would you call them an indie artist? I guess so, just because she's pushing the envelope on the sonic structure of pop music and I still think she's just amazing, and her evolution has been really fun to watch. I love Frank Ocean. Every new record, I'm always blown away by.

I mean, I could keep going. I listen to, as I said, you know lots of great stuff. There's no shortage of amazing music. When people say "People aren't writing great songs anymore," it's just not true. It's harder, though, in this really democratized marketplace, to find things that you might like.

When we were kids, the only way you could hear new music was essentially to buy records, or find some obscure radio station, or meet somebody who was like, you know, a Yoda of music history that you could hang out with and they could turn you on to things, and now you have like the celestial jukebox, right? You turn on YouTube, you can learn how to play any guitar figure. Stumping Spotify is kind of a fun game. There's times where I've got things in my vinyl collection which haven't been converted over to Spotify, and it's like "Yes!"

Pretty much kids can listen to anything right now, and I think adults sometimes just get kind of overwhelmed. It's much easier to go back and listen to those classic albums that with repeated listenings, you loved, and they still remind you of your life years ago. I don't know where I was going with all of that, but just the indie artists of today, there's a lot of exceptional music.

And I would also add that in the Twin Cities, a city that has a storied musical past between Prince and Hüsker Dü and the Replacements and Soul Asylum and yada yada,, this place continues to produce great artists. And part of it, I think, is that there is an expectation the city has, but I also think it's just fairly affordable for people to be here. And there's a great intersection of venues and radio stations and kind of the infrastructure that supports music along with record stores and things like that. So if I had more time and energy, I would be going out and seeing bands every night. There's just no shortage of great stuff here.

I was going to say at some point, I know you're not all in the same city, but it sounds like most of you — I don't know about Houston, but most of you are lucky to be in music cities. I think that makes a big difference in terms of how well you can support yourself with music.

Right. Tommy, who lives in Houston, who's a big blues guy — which I've only really discovered in the making of this record, I didn't realize how much he's into it — but he's really gotten into kind of the history of and technique of Texas blues playing. But he's also a guy in the record industry. Tommy works for The Orchard, which is a big distribution record company. So he's working with artists, strategizing on record releases and things like that. And he pretty much got us our record deal with a series of emails to people that he knew in different places, and sort of found people who were interested in putting a record out by what I would consider like a semi-legacy artist or something that isn't going to have huge expectations about record sales and all that.

So we managed to find a record label, Jillian Records, that basically has done PR for us and radio. And these were all things that we had to pay out of our own pockets before. We had to self-create a budget for radio, and press, and paying for the artwork, and connecting with Ma and Pa record stores — all that stuff we had to do ourselves, and this time around was kind of like old school. We have check-ins with the label every couple days about everything. They're monitoring radio stuff around the country. It just feels nice to have, for the first time in a while, the infrastructure around us even if it doesn't it doesn't amount to a huge amount of record sales. It's just nice that we've got a team of people who believe in this record and want it to go as far as it can.

That makes an awful lot of sense. It's been a while since I heard a veteran artist say that they're happy to be back on a label. Most of the time it's like, "Well, what do I need a label for? I can just do all this myself." But by the same token, as you mentioned, artists are being burdened with so many more responsibilities. Now artists have to be one-stop shops for everything, and it gets exhausting.

That being said, the indie part of the creative economy where you have to do all of those things you do, you're forced to learn how stuff works. So I'm grateful that we've had this long period of time since the fall of the major labels in the late '90s and early aughts that's forced us to understand how all of these parts work together. But again, it's just nice to have a little relief from having to take care of everything myself. It's enough to do social media, you know?

So then what is your incentive at this point for putting your music on Spotify? If you know the nuts and bolts, you know how everything works, what do you get back from having it out there other than, you know, three-tenths of a cent per stream?

I would say there's a bit of acquiescence around it, just saying, like, everybody's doing it. Yeah, the metrics suck, the monetization blows, but there's just not another option. Show me something else and I'll do it. And you know, there's a number of artists that have taken their stuff off and are just making their music exclusive. And I think for a really large artist that makes sense, but for an artist at our level where we need all the help we can get in terms of making our music accessible, I'm willing to forgo payment with this notion that we're part of that celestial jukebox, you know, like we're up there with everything, even though we might be harder to find than the Eagles or something like that.

Yeah, those damn playlists, man. That's a racket. Getting your music on "Laurel Canyon Grooves" or whatever. I don't know how much people are paying for those, but some of that music is just not that great. And it manages to land on these lists.

I look forward to seeing what you guys are going to come up with here. It sounds intriguing,