A Richer Way to Experience Music

"Speaking our truth loudly is the thing that actually helps love spread."

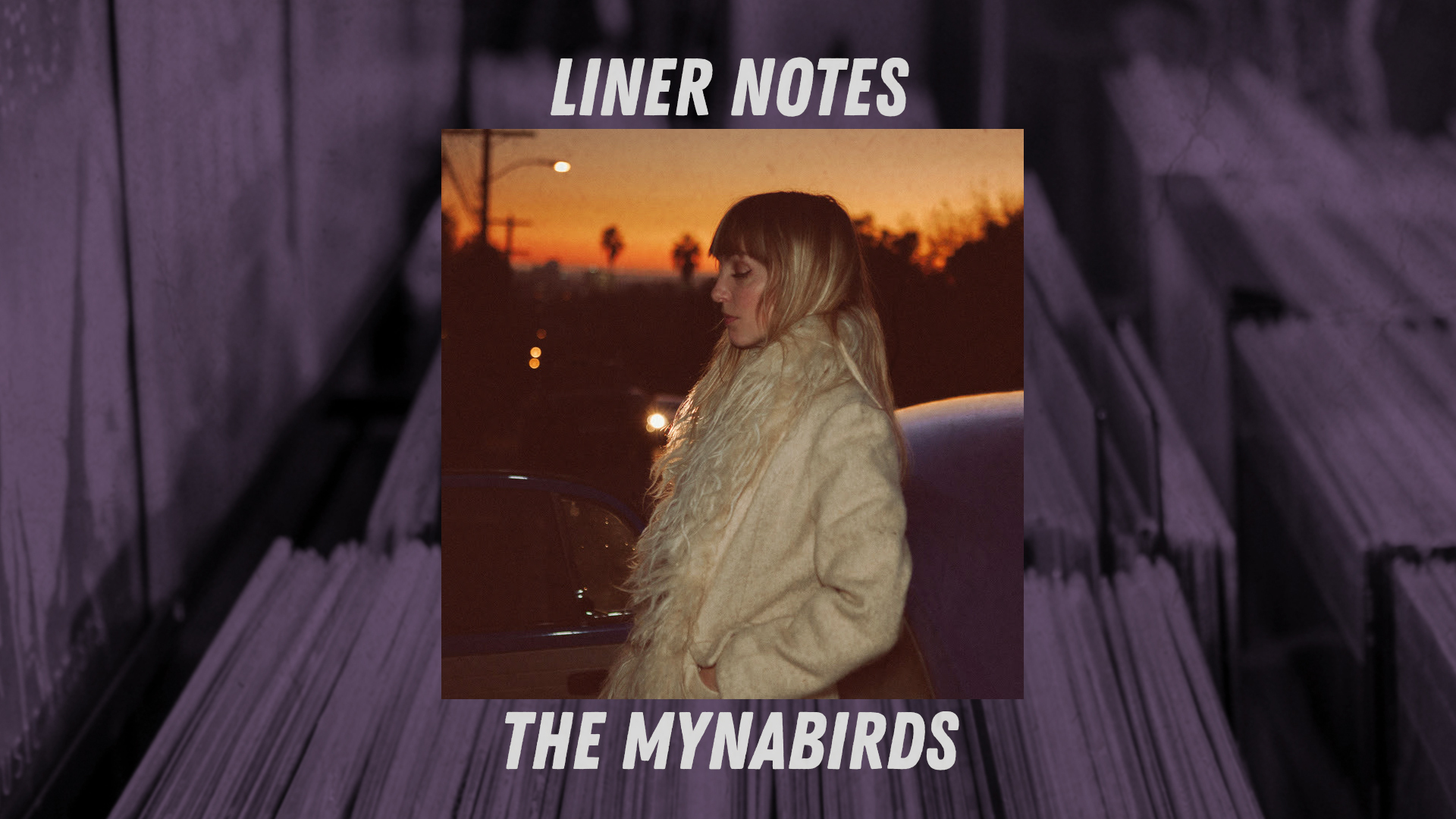

With her new album, the recently released It's Okay to Go Back If You Keep Moving Forward, Laura Berhenn — a.k.a. Mynabirds — revisits and reinterprets corners from her acclaimed catalog while also offering her first new songs following an eight-year hiatus. Like the title promises, it's a record that reflects on the past from a position of greater clarity while resolving to move forward into the ever-uncertain future.

Berhenn was gracious enough to join us for a wide-ranging conversation about the creation of her new album, offering a series of insightful observations about the modern music industry — and life in general —along the way.

I've been listening to this record a lot lately, and I think it's beautiful. But before we get into the music, I want to talk about the story behind how this happened, because I think there might be things to talk about there in terms of our relationship with the muse. I want to know if you'd ever been through this type of period before, where you felt like that switch was turned off and nothing was coming, and maybe nothing ever would.

I hadn't, actually. You know, I had heard so many people, so many artists, musicians, visual artists, talk about writer's block, right? And in some ways, I thought I understood what writer's block was. We all know the Simon and Garfunkel song "Cecilia," right? Which is ultimately about the muse, and where has she gone? You know, she's our lover one day and then the next she's gone, and we're begging her to come back.

So I thought writer's block would feel like that, but this period was so different. And as I came out of it — I actually have chills speaking about it. I think that just you asking the question struck such a deep nerve with me. It reminded me of hearing about Maya Angelou talking about a period in her life where she literally didn't speak to anyone for years in her childhood. And it was a response to sexual abuse as a child, you know? And I think that it's not just the muse that sometimes goes away, it's literally the voice of our soul. It's like the voice of what we're meant to say with our lives. So maybe that's a deep way to jump in very quickly. We jumped straight into the deep end. But I think that for me, that's what it was.

What I've realized over the period of eight years of silence is that music, for me, is medicine, and It's something that I have used throughout the course of my life as therapy that helps me through periods of depression. I credit it for saving my life a million times. I think that period of silence was about reconnecting to that deep voice of my soul.

Yeah, I believe that. I used to write songs, and there was a period leading up to the end when I was really trying. I eventually got to a place where I asked myself, "Well, what if I don't have to? What if it's okay if I don't?" And that felt very liberating, so I wondered if there was a period when you were really pulling at it and trying hard and not finding it there, and if that was scary for you or difficult in any way. And you have this other avenue that's also creative, so I wondered if you felt that sense of sort of peace and liberation in finally saying "Maybe this is the path that I'm meant to go down."

Absolutely. I felt the peace and liberation immediately, which was really the truth. Yeah, you know, I started a production company in 2018, and I started producing music videos. And during the pandemic, in a time when I thought that it was going to dead end, it actually got very, very busy, and I found such great satisfaction. I've gotten to work with such incredible musicians. Some of them are friends that I already knew through the music industry, like the War on Drugs. And some of them are icons, like Ringo Starr and blink 182 and like people I never thought I would necessarily be working with. And I was actually getting paid by the music industry, which as an indie musician, it was like, "Woo, I can relax for a little bit." I never really felt fear. I always kind of thought the unconscious mind is working some puzzle out, so even if I don't feel music coming, maybe it will eventually, or maybe my time as a musician is up. And this idea of song, what is voice, what is song? And there are all kinds of different ways that I think people send out their vibrational energies in the world. We are all singers in different ways.

And so I definitely felt that liberation. Yeah.

And like I said, I think I was sort of like, "The subconscious will come back around if and when she wants to," which is really, I guess, what I think the muse is — the subconscious mind. And for me, it's also tied to the collective unconscious. And I think that as I was sort of dealing with looking back into some personal traumas that maybe I hadn't addressed and feeling the disease of the collective consciousness in the past eight years, which has been a wild ride, I was like, "Music is calling me back. I have things that I need to sing for my own sanity and hopefully for in ways that feel healing or helpful to others."

We have been in trauma for many years now, and the thing that I really love about your work is its sincerity at a time when just being sincere is a major choice. I don't know if you've ever heard of a singer-songwriter named Matthew Ryan, but at one point we were talking, and he said "I just want everyone to win." That's the energy that I think we don't have enough of, and it's the energy that I get when I read about what you're doing. Not just through your music, but everything you're pursuing.

You know, this is going to sound so silly, but when I made the record Generals in 2012, I was asking... you know, it was a concept record, and the thesis of the record was, why do we fight? Why do we war with one another? What is it in us — is that just human nature? Is that something we can change? And what is the answer? And the answer I came up with is love. And it sounded so idiotic to me at the time. I was kind of embarrassed about it, but I was like, "No, I think that's true."

I was raised in a fundamentalist Christian church. When I was 13, the pastor got up and said, "Hey, I want to let you know we had gay people who came to the church last week. They thought they're welcome. They're excited to join. But I want to be very clear: They're not welcome, and they're going to Hell." And at 13, I thought, "Wait a second, you also taught me that God is love." And that's what I actually believe is what the world is made of and can be.

It's really that simple. It really is that simple to me. I think I understand why people want to be raptured. We are in hell right now. We're all looking for a savior to come along and lift us up and carry us like the footprints in the sand, that old Christian thing. We want someone to carry us. But the truth of the matter is that... what's the saying? Faith without works is dead. I forget who said that, but I resonate a lot with Thích Nhất Hạnh, who is an engaged Buddhist who came out of the Vietnam War, and watching the tragedies of that. And who said, basically, "I believe we can create a heaven on Earth, but we have to work for it."

And so in my mind, that's what I'm here to help remind people of. Through my music, it's about reminding people that each one of our individual voices, as sincere as we want them to be, that speaking our truth and speaking loudly is the thing that actually helps love spread. And maybe that sounds idiotic, but I think that's okay.

I think these days, we're meant to feel ashamed for any emotion that isn't anger.

Ooh. That is correct, especially grief. I think the pandemic revealed this deep grief that we were all in. Everybody was like, "No, no, let's get back to work. Let's get back to being productive." That's what I felt in myself in 2021. That was the breaking point for me, when I was in the middle of like 18 different productions. I was in North Carolina on an Animal Collective shoot, and my partner called and said "Your dog is really sick. You need to come home right now."

It was a month after my best friend had died. Suddenly, I found out my dog had a brain tumor and he had a month to live. I was making the most money I'd ever made in my life, but I was killing myself. My grandmother died in January of 2022 shortly after that, and I just was like, my god, life is so precious and so sweet and when we don't prioritize our healing and our care for ourselves and one another, are we really even living?

Before releasing It's Okay to Go Back if You Keep Moving Forward, you released "Labor Day Love Letter," a spoken-word single explaining why you were removing your music from Spotify. I talk to a lot of artists about their reasons for keeping their music on streaming platforms despite the lack of financial reward, and the answers are pretty mixed — some people are kind of like "Well, show me something better and I'll do that," and others seem almost ashamed to expect that they should be paid for their art.

I don't know how to get at the fundamentals of what I'm really trying to ask you about here, but I think there's something kind of telling about the tension between art and commerce that's always there — and how you found a way to get paid, but it wasn't nurturing you in the same way. And you had to kind of get off that hamster wheel as well. I don't know if there are any lessons that you take from that.

I think there's something parallel that really speaks to what you're talking about. And to go back, I've been releasing music since the early 2000s. I mean, technically, I think my first solo record came out in 1999, and I self-released that on CD Baby. It was a big deal. You could self-distribute at that time. You could self-press your own CDs. And Ani DeFranco was like my hero of someone who showed that you could do that on your own. You didn't need a label. You didn't need support.

And then we watched the rise of streaming platforms, which just made people earn less and less and less and less money. And here we are. Now this distribution platform is the system. This is what it looks like to distribute music in the modern era. But does it need to be, you know, do we want that to be our system? And I kind of looked at it and I thought, man, this system is devaluing everyone who's a part of it, and particularly musicians.

And so the parallel that I see is actually something that we witnessed in the wellness community and something that I witnessed with my best friend who passed. She became known as Guru Jagat, who was the head of the Kundalini Yoga Movement. And she spoke a lot about how as people in the world we should be entitled to money. It became this wellness thing that actually worshiped capitalism. Is that actually making us well or is that actually making us sicker? And she became very much a lightning rod of a person who I didn't really know anymore when she died. There's a whole HBO documentary about her called Breath of Fire. If anybody wants to watch that, I give an interview in it. But it's really interesting because, yeah, it's like we all continue to be full of dis-ease, I guess. I keep coming back to that word, dis-ease.

I decided that I wanted to remove my music from Spotify because I am not comfortable with the fact that Daniel Ek, the CEO, said "We can't pay you anymore." But somehow he made $700 million to invest in an A.I. military company. It's part of this eternal lie that the only thing that can stop war is more war, or the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun, and I just will not participate or perpetuate that lie with myself and my music and my efforts and my labor.

So that's the way that I've chosen to say I'm not going to wait until somebody shows me something better. Participation is perpetuation. And that is how I believe we perpetuate harm. And if I have to be the first person who steps off the hamster wheel and, again, doesn't make any money from the music industry, that's fine. In some ways, I kind of want to reject money in some way to say, "What are the other ways that I can find value in music?" And to me, that's in community. That's in using my platform to help raise money for nonprofits that support immigration, that support people who are barely surviving genocide. That's how I feel worth. Goddamn, it makes paying rent hard. But that's okay. You know, that's okay. Somebody's got to do something different, and I'm going to try.

I would love to think that at least a part of the anti-streaming, anti-Spotify sentiment that we're seeing is — even if subconsciously — rooted in the realization that streaming also devalues the listener. Because the listener becomes not so much a listener but a unit of attention for a business that isn't really distributing music, but just trying to accrue as many units as possible.

Because that helps them earn ad revenue, and that helps them earn other revenue. And what they found, Spotify specifically, is that the more music that they feed you that feels like background music, the longer you will listen. And so they're then platforming easy listening, essentially. There are even musicians who have fake bands, you know, who make this sort of stuff because they know, well, this is just how it is. And of course now we have fully AI-generated artists and Spotify says, "Ooh, that will hold people's attention, and we'll platform them because they're not going to fight for workers' rights." They're not going to go on tour. They don't need to pay their rent.

I have a real controversial opinion. And this was kind of formed in the Napster days, which is when so many musicians were so angry. Like, how could people think that music should be free? Right? And on one hand, I agree with that. And on the other hand, I think, wow, people feel that music should be free because music is so important to us that it should just be integrated into our lives. We all need it in the same way that we need water. It's like a natural resource that we need to consume to stay alive.

And so there's actually something very beautiful about that. But in the same way that we now pay for water and we pay for the internet — which is basically our desire to be connected to one another, right, across time and space. And so I think that unfortunately, governmental systems are fully integrated with big business and capitalism. And so therefore it all has to make money. But there is a different way. We could say, "Hey, these are all natural resources that everybody deserves to have as human beings. We deserve the right to have water and music and food. And let's figure out a system where we pay the people who make those things and where we protect the water sources so that we have enough for everybody." We don't currently live in that world.

Can I interject one quick thing that this also brought to mind, which is that I've known a lot of artists who became Spotify, TikTok, Instagram famous, you know? And as a person who's been making music for a very long time, and I've never paid Instagram to have more followers, never engaged in any of that stuff, sometimes I look at my metrics and I think, gosh, this really is sad, you know?

But last year I decided to go on tour for the first time in six years, and I was able to play to full rooms — they weren't huge rooms, but they were very meaningful experiences with people who had sat with my records and had listened to them. I had people who came up to me and said "Lovers Know saved me after my divorce," or, you know, "I played this one song at my wedding."

These were moments where I got to be involved very deeply with people in their intimate moments in their lives, and that was so wonderful to me. And in the meanwhile I've watched artists who've had these flash in the pan successes that looked good at the time, and now they don't have anybody really listening because was anybody really listening to start with, or were they just looking for the next thing, or were they just listening passively as they were going through their day?

Whatever that artist made was very beautiful, but it wasn't necessarily something that the listener ended up having an intimate relationship with, and that's very sad to me, because all of those artists deserve those kinds of deep connections. Because they are making beautiful art.

Right. Right. The type of instant success you're talking about is what's held up as the brass ring, but what it really is is that act of communion you're talking about between the artist and the listener.

You also mentioned community, and I think that's another thing that people are realizing that has sort of been dribbled away from the internet. It was once a really fun way to find like-minded people, and now it's just kind of social media and ads, and I think people are starting to understand that they've lost something there. They do want community. But this is not something that scales, and I think scale is kind of the enemy of creative endeavors in a lot of ways.

For artists, instead of wanting to be influencers or go viral, the real goal is to connect as strongly as possible with the people who are waiting for your voice. It's hard and it takes a long time to find them, but I think that's what matters.

Absolutely.

Before we run out of time, I want to ask you something else about this record. You went through a period of silence, and you felt at peace with that. And then you endured grief, and the spigot opened again. But it seems like it wasn't the opening of a floodgate. You have a few new songs on this record, but primarily, you went back to older songs and reinterpreted them. Is that because the songs didn't just come pouring out? What led you from "Here's the first song I've written in a long time" to "I'm going to make this album in this way"?

It's so hard to even know how to answer that question, because there's a lot of mystery around it that I don't totally understand. I went with it because it felt right, you know, and I think that part of it was that I've I've released four records before this one, and kind of felt disappointed in some ways, felt like a failure. You know, I started out playing at the same time and on the same bills and featured in the same magazine articles of artists to watch like Florence + the Machine, Mumford and Sons, bands that have gone on to become huge. Nathaniel Rateliff, he and I know each other because we both made records with Richard Swift and we will forever be siblings because of that. He's enjoying such a huge moment with his music in the Americana world and I'm so happy for him, but in some ways I looked at my own career and thought, "My god, I've failed. I've totally, totally failed."

To come back to music, it was like, why did I start making music to begin with? And it was sort of this act of, like I said, therapy for myself. What am I singing? What makes my songs unique? What am I bringing to the world that nobody else could? And I have to believe that there's value in that. And I hope that everybody who creates, who makes anything, understands that there's value in whatever they're making from their unique voice.

And so I think part of it was like, let me get right with my music, my relationship with music, let me get right with my relationship with voice, and let me look back on what I've made and think about those pieces of music that I think right now in this moment are necessary to my mental health and to our collective consciousness, the collective consciousness' mental health. And that's why I think those songs came forward. We actually recorded 16 or 17 songs total. Out of 10 of them, three are new and seven are "old," you know, out of the ones that made it onto the record.

I just led with my gut and I thought "These are the songs that are coming forward right now that want to be heard." I remember hearing Tori Amos talking about each of her songs coming. They would either come forward or they wouldn't, they'd be shy, and it was a question of which ones were going to come to the piano that night. And that's kind of how she crafts her set lists when she plays live.

I really was like, no, she's right. Each one of those songs has its own little spirit. And honestly, in the way where you, if you ever do any therapeutic work and you're like, "I'm going to go back and work with my inner child," each one of those songs came forward in a way that was like, "Hi, I'm this inner child that needs to come forward and be heard."

Tori Amos is one of my greatest inspirations, Nina Simone is one of my greatest inspirations, and I really had to think about who deeply inspired me and how can I honor not only them, but the lineage of their voices through time. And a lot of them were huge civil rights activists, people who really used their platforms to fight for others as well as themselves. And so that's how those songs all got chosen.

I felt like it was me getting right and getting realigned in my life. I will continue to produce things for other people, and I love the work I get to do with my production company. But also I had to say, "What am I here to do in this life? I need to get right with that." And so maybe the next thing that comes, the floodgates open and there's some big album that comes next. But I couldn't get to that without going through this first.

That makes a lot of sense. I was going to ask as a follow-up if you have enough perspective yet to know how this has changed your relationship with the muse, with music, with songwriting.

I think that in some ways I've given up control and I can look back on my career as a musician and see the ways in which every song was an honest expression. Every song came from someplace in my heart. But also I can look back and see the ways in which I was trying to say, "I think people will like this if I do this." How do I get people to like me? How do I get people to heart my post, or thumbs up my song on a DSP? That part of our personality that is totally built on needing and wanting to be liked... there's nothing wrong with it, but please, don't let that drive everything we do. Part of this is a practice in becoming unlikable.

It's like, this is simple, this is slow. If this is not your thing, that's okay, skip past. I don't care. But if it is your thing, thank you so much for listening, and I hope it really means something for you.

Beautiful. As a parting shot, and I didn't prepare you for this, but one thing that we usually ask people is if they can recommend a handful of indie artists. I don't know if you're listening to anybody right now, or if you can do that. I would be flat-footed if somebody asked me right now.

I always hate these questions because usually it feels like having to show your record collection, and I always get so nervous about being judged. Because I don't give a shit about being liked right now, I'm going to answer very honestly. I really love all of the records that Andy Shauf has made. I think that he is just such an incredible storyteller. And honestly, listening to the ways in which he is so quiet and so fully himself, I think, gave me a lot of courage to come back and say that songs can be songs. They don't have to be anything but that.

I have so many incredible friends who are making beautiful music in this time, so I want to take an opportunity, because I think that's really what we need, is a beautiful network of support. Casey Dienel, who's put out putting out a beautiful record; Doe Paoro, who's putting out a beautiful record. And we're actually talking about starting a podcast ourselves. Each one of us has made such a different expression of our own journey, and that's really cool to hear. And it's really cool to support different people.

Kadhja Bonet, love her to pieces. She and I have become friends through the Disarm Spotify movement. She's gone one step further than me, and she's not releasing music on Apple or Amazon or YouTube because she's like, "They're all tied to war, and I don't want anything to do with them!" So I deeply appreciate her. And honestly, what's hilarious is that I actually found her music first through Spotify radio. A song was fed to me.

The algorithm can be useful sometimes, right?

Yeah, have you seen the Brian Eno documentary? This is a person that I think we all need to be looking to as a shining example of how to be a deeply curious and creative and consciously involved person in humanity right now. This documentary is so cool. Basically, Brian Eno was like, "I hate music documentaries, so if you want to make a documentary, we have to come out with a new way." The director said, "OK, we're going to log 800 to 900 hours of footage and we're going to create an algorithm that will make it so every time the movie is shown, it's a different cut." The algorithm goes in and chops it up and turns it into something different, so the viewer, everybody who's in that room, it's like being at a show where you only get that one performance that one time.

And so I just am so inspired by him. I happened to watch it the same night that he was hosting the concert for Palestine at Wembley Stadium, so it was like this beautiful intersection of what it means to be curious and act in the world with love and use technology in really interesting ways. And he's such an environmentalist, he won't even fly. He won't get in an airplane. So I think he's probably not interested in AI. But he was like, "The algorithm is cool. We can do something cool with this."

Yeah, let's listen to more Brian Eno. Not just his music, but his way of being in the world.